Dracula was a macabre milestone in my development.

In 1991, aged nine, I was lucky enough to get a spellbinding tome: a double edition of Dracula and The Phantom of the Opera. I bought it from my primary school’s book fair and was instantly enthralled and horrified by Stoker’s work. The edition’s central conceit was that the two tales were printed upside-down in relation to one another, and for some reason I thought that was supremely cool. The Phantom of the Opera was a good story; I particularly enjoyed the phantom’s visit to the ball. But it didn’t terrify me.

In 1991, aged nine, I was lucky enough to get a spellbinding tome: a double edition of Dracula and The Phantom of the Opera. I bought it from my primary school’s book fair and was instantly enthralled and horrified by Stoker’s work. The edition’s central conceit was that the two tales were printed upside-down in relation to one another, and for some reason I thought that was supremely cool. The Phantom of the Opera was a good story; I particularly enjoyed the phantom’s visit to the ball. But it didn’t terrify me.

Dracula did.

Before reading Dracula I was interested in GI Joe and Transformers. Afterwards I demanded culture with a darker side. I distinctly remember hiding the book in a cupboard one evening in my aunt and uncle’s room. I had been reading it in my cousin’s bedroom until I got too scared. Their house was wonderful, a four-storey treasure trove of interesting items, but it was also big and old and quite lonely at the top of the fourth floor. The scariest part of Dracula for me were the dancing motes of dust which crept under the lintel and hypnotised the stiff young lawyer, Johnathan Harker. Even aged eight I was fairly sure that vampires didn’t actually exist, but dust motes certainly did, and I was completely freaked out by the prospect of them attacking me.

But however horrified I was, I couldn’t stay away: I re-read Dracula at least a dozen times. Thinking back, it’s somewhat of an odd choice for a child’s book fair edition – Stoker’s prose style is ponderous and – as we’ll see – it’s not by any means a story aimed at children. There’s also an unmistakable sexual theme which suffuses the book, and which completely bypassed me as a child reader.

But however horrified I was, I couldn’t stay away: I re-read Dracula at least a dozen times. Thinking back, it’s somewhat of an odd choice for a child’s book fair edition – Stoker’s prose style is ponderous and – as we’ll see – it’s not by any means a story aimed at children. There’s also an unmistakable sexual theme which suffuses the book, and which completely bypassed me as a child reader.

The next year, Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula was released. There was no prospect of seeing it at the cinema; it had the tantalising and terrifying 18 certificate. There were a few kids at school who boasted about seeing 18s at the cinema – one lad claimed his dad had hidden him under his coat to bring him in to see Robocop – but more were seemingly allowed to watch whatever they wanted on VHS, often under the auspices of impossible cool older siblings. I was the oldest in my family, and my mother was resolute: no films we were too young to legally view. She was wise to insist. I had an overly fertile imagination as a youngster anyway, and would probably have been scarred for life by watching Terminator or Pumpkinhead.

Still, I devoured anything Bram Stoker’s Dracula-related, which, pre-internet, wasn’t much: a review in the Sunday Times and a short-lived (and gruesome) comic. The film was panned by the Times and I tried to convince myself that I hadn’t missed out. I forgot about it. In fact, it got such a negative critical response that for many years whenever it popped up I never even considered watching it.

That was an oversight. In some ways, it’s a masterpiece.

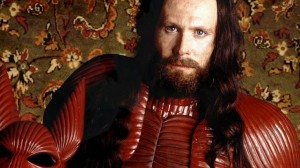

The storyline is confused and illogical; the script is dull; and most of the performances leave something to be desired. None of that matters. Even with all of these flaws, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a singular achievement. The costumes won Eiko Ishioka a deserved Oscar, and the baroque inventiveness and sly playfulness of her work is astonishing. Count Dracula lives in a crumbling castle, but is consistently decked out in twisted finery. His red battle armour, looking so much like flayed skin, is instantly iconic, and though there’s a flamboyant theatricality to many of his other outfits, it’s not at all camp or kitsch; he’s male, masculine and authoritative, despite his huge, dress-like, combination mantle/dressing gown, ponytail and bouffant “at home” hairstyle, and shimmering grave clothes, and it’s to Gary Oldman’s huge credit that he still makes the Count nuanced, frightening and human while encased in these creations and makeup (the film also won Oscars for makeup and sound effects). Oldman’s genius is in revealing glimpses of tenderness, playfulness and mischief in the Count, despite his being unremittingly evil and selfish. He’s not just an evil demon. He’s still a man. I don’t worship Oldman, but here he brings a genuine range of emotion and expression to his part. Marching to war with the Turks, the Count is circumspect, seemingly shaken by the horrific responsibility placed on him, though he rises to the grim challenge. As an old man, despite his bloodthirstiness and corruption, there’s something charming and fragile about him, even though it’s made clear that he still possesses extraordinary physical and supernatural attributes. Rejuvenated by blood as the film continues the middle-aged Dracula is seductive and charismatic, while remainig fundamentally damaged by the sadness he’s endured and the atrocities he’s committed. He is evil, but not irredeemably so. After all, the key driver of Dracula’s conversion to darkness (or darker darkness) was the purity of his love for his centuries-dead wife, Elisabeta, to whom Mina Murray bears a striking resemblance (both characters are played by Winona Ryder), and there must have been some portion of him that was good for love to have played such a pivotal part in his embrace of the unlife.

The storyline is confused and illogical; the script is dull; and most of the performances leave something to be desired. None of that matters. Even with all of these flaws, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a singular achievement. The costumes won Eiko Ishioka a deserved Oscar, and the baroque inventiveness and sly playfulness of her work is astonishing. Count Dracula lives in a crumbling castle, but is consistently decked out in twisted finery. His red battle armour, looking so much like flayed skin, is instantly iconic, and though there’s a flamboyant theatricality to many of his other outfits, it’s not at all camp or kitsch; he’s male, masculine and authoritative, despite his huge, dress-like, combination mantle/dressing gown, ponytail and bouffant “at home” hairstyle, and shimmering grave clothes, and it’s to Gary Oldman’s huge credit that he still makes the Count nuanced, frightening and human while encased in these creations and makeup (the film also won Oscars for makeup and sound effects). Oldman’s genius is in revealing glimpses of tenderness, playfulness and mischief in the Count, despite his being unremittingly evil and selfish. He’s not just an evil demon. He’s still a man. I don’t worship Oldman, but here he brings a genuine range of emotion and expression to his part. Marching to war with the Turks, the Count is circumspect, seemingly shaken by the horrific responsibility placed on him, though he rises to the grim challenge. As an old man, despite his bloodthirstiness and corruption, there’s something charming and fragile about him, even though it’s made clear that he still possesses extraordinary physical and supernatural attributes. Rejuvenated by blood as the film continues the middle-aged Dracula is seductive and charismatic, while remainig fundamentally damaged by the sadness he’s endured and the atrocities he’s committed. He is evil, but not irredeemably so. After all, the key driver of Dracula’s conversion to darkness (or darker darkness) was the purity of his love for his centuries-dead wife, Elisabeta, to whom Mina Murray bears a striking resemblance (both characters are played by Winona Ryder), and there must have been some portion of him that was good for love to have played such a pivotal part in his embrace of the unlife.

In contrast to Oldman’s performance, Keanu Reeves’ (Harker) and Winona Ryder’s (his fiancée, Mina Murray) acting was justly criticised by reviewers at the time – Reeves is laughably wooden – but somehow it works. In the book Harker is upright, devoid of imagination, a cipher; he is Dracula’s opposite in every sense, and Reeves’ hollow portrayal is the perfect foil to Oldman’s multi-facteted Count. Reeves’ performance goes beyond amateurish; his Harker is missing some essential curiosity, some ability to be entranced, which makes him, actually, a credible vanquisher of the ancient evil. And if Ryder’s performance is somewhat one one-dimensional, one could hardly claim that it deviates from the pulpy flatness of her portrayal in the book. There’s an essential sweetness to her performance which captivates, even when she is exploring the sexual impulses the Count awakens in her. More importantly, she is luminously beautiful, and it doesn’t stretch credibility that her resemblance to the Count’s lost wife of many centuries previously would lead him to concentrate his dark energies on possessing her. This is a film, after all, and the visual element is the most important. I don’t know anything about cinematography but the camera angles and lighting are immensely evocative and effective, with the exception of the montage sequence showing Dracula’s journey across the sea to London, which is quite cheap and shoddy (perhaps it’s a homage to a classic film), and the asylum scenes, which are quite obviously filmed on a soundstage.

In contrast to Oldman’s performance, Keanu Reeves’ (Harker) and Winona Ryder’s (his fiancée, Mina Murray) acting was justly criticised by reviewers at the time – Reeves is laughably wooden – but somehow it works. In the book Harker is upright, devoid of imagination, a cipher; he is Dracula’s opposite in every sense, and Reeves’ hollow portrayal is the perfect foil to Oldman’s multi-facteted Count. Reeves’ performance goes beyond amateurish; his Harker is missing some essential curiosity, some ability to be entranced, which makes him, actually, a credible vanquisher of the ancient evil. And if Ryder’s performance is somewhat one one-dimensional, one could hardly claim that it deviates from the pulpy flatness of her portrayal in the book. There’s an essential sweetness to her performance which captivates, even when she is exploring the sexual impulses the Count awakens in her. More importantly, she is luminously beautiful, and it doesn’t stretch credibility that her resemblance to the Count’s lost wife of many centuries previously would lead him to concentrate his dark energies on possessing her. This is a film, after all, and the visual element is the most important. I don’t know anything about cinematography but the camera angles and lighting are immensely evocative and effective, with the exception of the montage sequence showing Dracula’s journey across the sea to London, which is quite cheap and shoddy (perhaps it’s a homage to a classic film), and the asylum scenes, which are quite obviously filmed on a soundstage.

One area where neither Ryder nor Reeves can be criticised are their English accents, which are impeccable, although I get the impression that Reeves in particular was concentrating so hard on his diction that he was unable to spare much thought to performance. On the other hand Oldman’s accent when he speaks English is a hackneyed pastiche of Bela Lugosi and Ivan Drago, but again, he underpins it with such a strong and subtle performance that it doesn’t matter. (In my experience, it’s actually Bulgarians who tend to have the stereotypical Eastern European accent; Romanians – speaking a Romance language very similar to Italian – typically have a softer English accent.) The film makes some use of Romanian, and it’s another lovely touch; I can’t stand Hollywood films where speakers of another language are standing around talking to each other in accented English.

One area where neither Ryder nor Reeves can be criticised are their English accents, which are impeccable, although I get the impression that Reeves in particular was concentrating so hard on his diction that he was unable to spare much thought to performance. On the other hand Oldman’s accent when he speaks English is a hackneyed pastiche of Bela Lugosi and Ivan Drago, but again, he underpins it with such a strong and subtle performance that it doesn’t matter. (In my experience, it’s actually Bulgarians who tend to have the stereotypical Eastern European accent; Romanians – speaking a Romance language very similar to Italian – typically have a softer English accent.) The film makes some use of Romanian, and it’s another lovely touch; I can’t stand Hollywood films where speakers of another language are standing around talking to each other in accented English.

Another striking aspect of the film which I completely missed as a child is just how low the stakes are. Dracula isn’t set on world domination; he simply wants to, well, get with a woman who looks exactly like his centuries-lost love (a woman who has at least some affection and attraction to him, it must be said). As a child reading the book I was petrified at the thought of the Count escaping justice; watching the film, I just want Dracula and Mina to swoop off into the twilight together.

Another striking aspect of the film which I completely missed as a child is just how low the stakes are. Dracula isn’t set on world domination; he simply wants to, well, get with a woman who looks exactly like his centuries-lost love (a woman who has at least some affection and attraction to him, it must be said). As a child reading the book I was petrified at the thought of the Count escaping justice; watching the film, I just want Dracula and Mina to swoop off into the twilight together.