- America

This month Swimming In Blood is released, the ninth volume in the Judge Dredd Mega Collection partwork. The Mega Collection has been spotty to date, but Swimming In Blood stands alongside the very first volume, America, as a classic of sequential art. Here are some thoughts on both works.

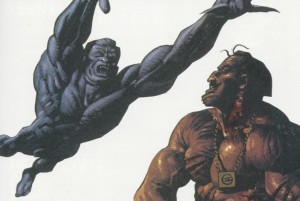

America, by John Wagner and Colin MacNeil, details the tragic love story of America Jara and Bennett Beeny, two Mega-City One kids who’ve grown up together. They drift apart, America devoting her life to underground, increasingly violent agitation for a hard-line democrat group, while Bennett finds huge success as a singer of novelty comedy numbers. Despite the acclaim he’s gained, he is deeply unhappy, never having recovered from losing America to the political struggle she’s pledged herself to. To say any more would ruin the tale, but Dredd – present only as a supporting character – is still centrally important to the story. America was one of the first Dredd stories to flesh out the stone-jawed lawman somewhat. This Dredd is angry, vindictive, uncertain and clearly not fully in control of the situation. He makes difficult decisions where there’s clearly no best option. He doesn’t engage in any of the unbelievable invincible action-hero histrionics of most of his stories. You might presume that America would detail some kind of existential threat to the judges’ reign over Mega-City One, but that’s not the case: it’s made quite clear that the democrats are more-or-less doomed from the start, arrayed against the superior technology and numbers of the judges. And it’s not a simple inversion, either; the democrats are violent, unscrupulous and bitter. As the tale unfolds we get some direct narration from Dredd of his personal philosophy, and it’s fascinating. Anyone who’s read 2000AD for any length of time will have felt frustrated at Dredd’s archetypal nature, his unchanging, iron-hard worldview and two-dimensionality, so the glimpses we have here of Dredd as human (quite beyond anything published before or since, to my knowledge) are utterly compelling. It’s a familiar curse afflicting pretty much every franchised, non-creator-owned character; no publisher is going to want to kill off or radically change their property. The payoff is that while America has been highly praised as “one of the best Dredds ever”, I wonder if anyone reading it who’s never been exposed to 2000AD before wouldn’t feel slightly underwhelmed. Much of what makes it so exceptional can only really be understood in the context of what had been Dredd’s entire ouevre up to the point it was published, in 1990.

The volume collects every 2000AD and Megazine story dealing with America and Bennett and their extended circle, not just the original epic, and all of the follow-up stories are equally essential. Bennett’s robot butler, Robert, is written with such subtle skill and nuance that he turns into a starring character himself; gentle, principled and compassionate, some of his interactions with the other characters are genuinely affecting. The later stories introduce another character, a young judge who is mentored (in a fashion) by Dredd, and she too is handled with consumate grace by Wagner. Her story also gives a valuable insight into the nuts-and-bolts workings of the judges’ system – they can, apparently, re-consider the verdicts and punishments they have meted out, but only the judge who has given the initial judgement can do so, no matter how much bureaucratic pressure is brought to bear.

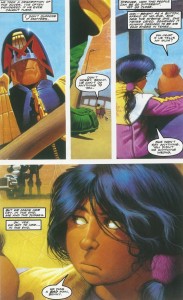

MacNeil’s art in the original story is fully painted and imbued with a warm, sunny haze that belies the darkness of the story while somehow fitting it absolutely; it reminded me of those thick, sticky summer days when we often begin our first excruciating lessons in love. Most of the later stories are drawn in ink and coloured by a colourist, and it has to be said that MacNeil’s style suffers somewhat from the switch, with his work in the first follow-up story in particular seeming poorly proportioned and almost childish. His artwork tightens up increasingly for the rest of the volume, until the very last story, a six-page one-episode reprint unconnected to America or Bennett (and written by Garth Ennis) which sees MacNeil return to painted art (this story was originally published in the early 90s, before any of the follow-ups). Despite its importance being best highlighted by the rest of the canon I would still recommend America as an introduction for anyone who hasn’t read any Dredd stories before, but they might then find much, or most, of the subsequent canon shallow and repetitive. That’s comics for you, I suppose.

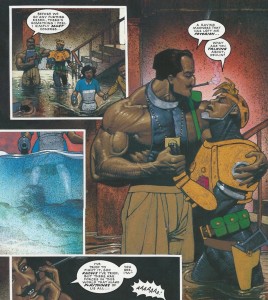

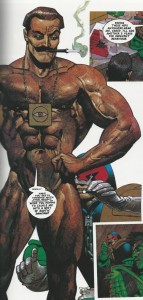

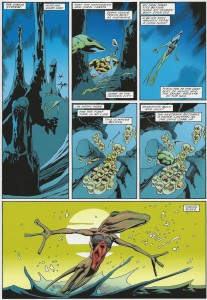

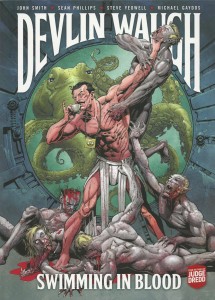

Swimming In Blood was the first story featuring Devlin Waugh, the homosexual Dredd-verse Vatican exorcist, and this volume contains the titular story and a number of later adventures. Written by John Smith and illustrated by Sean Phillips, Swimming In Blood one of the strongest things I’ve ever read from the 2000AD stable. It just works; Waugh is an instant classic of a character, and the story, though simple, is gratifyingly nasty. Waugh is a a muscle-bound English fop, expert at fighting occult menaces, and he is called in when an underwater prison is decimated by a vampire infestation. Most of the inmates and some of the staff are turned, with a small remainder relying on Waugh to lead them to safety. A very short article in the back of the volume reveals that Waugh’s name is a play on Evelyn Waugh, and though he could be likened to an amplified version of Brideshead Revisited’s Sebastian, I find him more like Bertie Wooster than anyone: knowingly petulant, superficially monstrously selfish, but essentially devoted to helping others, how ever much it annoys him. While taking stock of possessions he’s lost to the ocean, Waugh moans,

“Oh, the horrible unfairness of it all!

“Oh, the horrible unfairness of it all!

My every personal effect condemned to the ocean, and not one of you has shown the slightest scrap of sympathy!

I’m completely unappreciated. It hasn’t escaped my notice, you know…

Now. I shan’t lift another finger to help until I’ve had an apology from each and every one of you.”

Waugh is extravagantly, flamboyantly gay, too (something I couldn’t really cope with when I first read the story as an eleven- or twelve-year-old): leading a small group of survivors through the rapidly-flooding prison, hotly pursued by savage vampires, Waugh decides, apropos nothing, to declare his burning attraction for one of the prison’s guards, who is baffled:

“Before we go any further Essex, there’s something I feel I simply must confess…

A raving madness that has left me feverish…

I’ve tried to fight it, God knows I’ve tried, but there are forces in this world that makes playthings of us all…

You see, I’m - ”

He’s utterly compelling, a pitch-perfect mixture of hackneyed tropes which combine into a fresh and intriguing whole. There’s substance beneath the affectations too, physical and mental – Waugh is a supremely skilled fighter, and when he finally confronts the leader of the vampires, his scathing summation of the villain almost makes you feel sorry for a bloodthirsty monster:

“Well, well, well.

You must be our enigmatic Mr Landis…

I would like to say I’m pleasantly surprised, but I’m afraid you entirely live up to my expectations. Brutal and bloody and not very bright.”

Phillips’ artwork is the queasy flipside to Colin MacNeal’s shimmer; the work is bright too, with that same thickness which only comes from hand-painted colour, but there’s an injection of vivid grime here which is utterly suited to the tale – bright spots of blood on rusted ironwork and pulsing veins in torn skin. Waugh and the vampires are drawn as hugely muscled, but proportionally so; Devlin’s physique is realistic in that it resembles a world-class bodybuilder, tying in with a small reference in the story to his use and abuse of steroids.

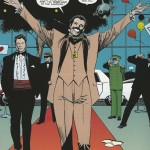

The rest of the collection is taken up with a short and satisfying single-issue story between Dredd and Waugh (Waugh goes to a cat show in Mega-City One) and two non-essential Waugh stories (one of which with artwork by Colin MacNeil), but if you’re really interested in more Devlin Waugh I recommend the 2014 collection Devlin Waugh: Swimming In Blood instead. It also collects the eponymous story and the short one-off with Dredd, but most of the volume showcases Chasing Herod/Plague Of Frogs/Sirius Rising, a very protracted world-spanning tale featuring Waugh teaming up with previous enemies to stop an occultist turning the earth into a new home for aliens from Sirius. It’s disjointed and confusing, and like many 2000AD/Dredd stories it ends with a kind of deus-ex-machina conceit, but despite all that, I enjoyed the story a lot; early on I decided to give up on forcing the plot to make sense and instead concentrated on appreciating the striking characters Smith comes up with. Smith seems to be almost parodying himself with the constant references to people and concepts which are only alluded to – Mr Bliss, the Cult of the Purple Fist, Mover: Gravers – and he performs his usual trick of introducing a character who is supposed to be world-endingly dangerous but doesn’t actually do much. (In this case it’s a Vatican operative called Pussy Willow. We’re told she’s an “Ultravixen” and “last hot spot she sanitised they were cleaning up body parts for a week” but literally all she does in the story is fly a plane through a psychic disturbance and report back on it quite helpfully.) There’s a a coterie of evil Jacks – the Jack of Knives, the Jack of Mice and so on, gene-cloned assassins who facilitate the schemes of the main villain – and all are supremely creepy and individually

disturbing. Also unforgettable are the rag-tag group of occult criminals, most of them very nasty, who end up allies of sorts to Waugh. The art is by Steve Yeowell, whose clean and assiduously-proportioned work couldn’t be more different from Smith’s, and with typical understated brilliance he gives the characters, as silly and one-dimensional as some of them may be, genuine personality: menacing, vulnerable or grotesque as befits them. My only gripe is that Waugh here looks a bit too ordinary; he may have come off the steroids (we’re not told) but he now looks like Terry Thomas. Halfway through the story we meet Devlin’s mother. Like her son she’s acidic and scathing but is far from the evil harpy I’d expected – Smith confounds expectations by combining her biting wit with sincerity, and concern. And the final page of the saga features a genuine rarity for a John Smith story: something of a happy ending, for one of the characters, at least.

The volume finishes with a short prose story by Smith detailing an obsessed fan who stalks Devlin. Having read this years ago when it was first published in the early 90s, aged about twelve, I wasn’t expecting much on my recent revisit; Smith’s comic-book work is so overwrought and full of purple-prose that I expected this purely textual piece to be poor on re-reading. It’s not poor at all: it’s a masterpiece. Smith’s writing here is simultaneously warm and horrifying, and the clever denouement has stayed with me. My only real gripe with the 2014 volume is the cover. Cliff Robinson is a great artist, but he’s wrong for Waugh. The composition, too, is silly – Waugh is over-the-top, but he wouldn’t drink a cup of tea while fighting multiple vampires (who are exceedingly dangerous, it’s made clear). This cover has more in common with the kind of desperately-unfunny comedy sci-fi caper strips 2000AD periodically prints – stuff like Time Flies and Survival Geeks. The Mega Collection cover isn’t much better, a rather camp effort with a side-by-side Dredd and Waugh, Dredd pointing a very phallic truncheon directly at the reader in what I assume is a winking nod to Waugh’s homosexuality (and perhaps Dredd’s own fetishistic design).